Vanderbilt Mansion- Hyde Park, NY

There were a lot of Vanderbilts, and they were all wildly wealthy. They all had several amazing homes, each grander than the last, and certainly built to be grander than other Vanderbilt mansions, of which there were over forty. In Hyde Park, Frederick Vanderbilt built a Neoclassical Beaux Art beauty, which perfectly showcases the excesses of the Gilded Age, and what is possible when money is no object.

Just to give a brief overview, the patriarch of the family was Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt, a self made millionaire who built a shipping and railroad empire in the early 19th century. He had 13 children, but left almost his entire fortune, $100 million, to son William. William in turn had 8 children, one of which was Frederick, who constructed the Hyde Park mansion. When William died in 1885, he left an estate of over $195 million to his children. Which goes a long way when the average annual income was around $500 dollars. So, there was plenty of money in the Vanderbilt family for grand estates, at least until income tax came along.

Built in 1896 by the illustrious architectural firm McKim, Meade, and White, the 54 room, 50,000 square foot mansion sits perfectly perched on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River. Designed in a stately Neoclassical style with Beaux-Arts detailing, the massive monolith incorporated all the modern luxuries of the day, including plumbing, central heating, and electric lights, powered by a hydroelectric plant located on the estate grounds. Stanford White personally crisscrossed Europe in search of treasures for the mansion, scooping up fine furniture and artwork from unfortunate families who had lost their vast fortunes. All in, the “cottage” cost $2,250,000 to build and furnish, a mere drop in the Vanderbilt bucket.

Inside, the seasonal country home was centered around an elliptical reception hall, with an octagonal opening above bringing in light from a second floor skylight. On opposite sides of the house sit the grand drawing room and dining room, each with windows facing the Hudson. The detail in each of the spaces is overwhelming, meticulously designed by several different firms. Intricately carved dark wood paneling is accentuated by ornate white plaster ceilings. Custom lighting by E.F. Caldwell & Co. lines the walls.

The public spaces are meant for entertaining and impressing; it did neither for the nearby Roosevelt’s who refused to attend any parties or dinners, despite being invited multiple times. The old money types found the Vanderbilts distasteful and crass. Indeed, FDR declared the mansion “a hideous albatross,” although I respectfully disagree. I will admit it is deliciously gilded and over the top. I will also admit I would not want Sara Roosevelt at any party of mine, as she just seems awful. Just ask Eleanor.

Although the staircase is somewhat subdued, relatively speaking, the second floor is equally as impressive. Indeed, Louise’s Ogden Codman designed suite is something straight out of Versailles. Literally. It was patterned after Marie Antoinette’s chambers, raised platform bed and all. It is indeed palatial, and fit for a queen. Frederick had his own suite of rooms, naturally, although not quite so ornate. Several guest rooms and baths occupy the remainder of the second floor.

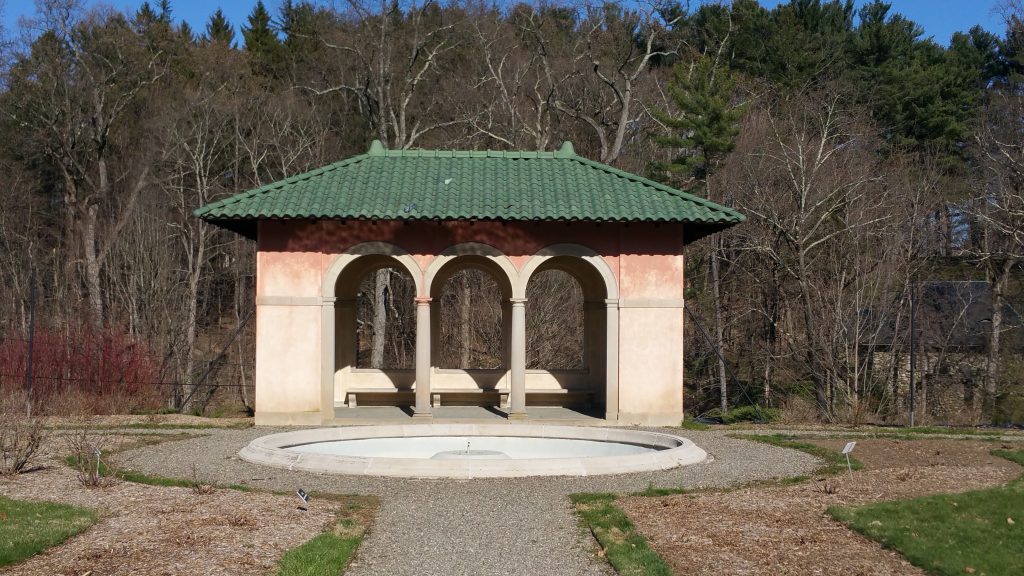

Outside, the estate is beautifully landscaped. First developed by previous landowner Samuel Bard, the grounds were planted with a variety of exotic trees and plants, including one of America’s oldest Ginko trees, which dates to 1799. Later owner Walter Landgon, Jr. added a formal garden, hiring a Boston landscape architect to design a gardner’s cottage, tool house and garden walls, which still exist. The Vanderbilt’s added to this design with a terraced garden, water features, statues and arbors. The rear of the estate overlooks the Hudson River. Indeed, the National Park Service maintains over 200 acres of the original property, which is free to explore, and includes one of the country’s first steel and concrete bridges.

When Louise died in 1926, Frederick sold off his other properties, and spent the remainder of his life at Hyde Park. Childless, the estate was left to his niece in 1938 when Frederick passed away. By this time, grand country homes were no longer feasible; income tax had been introduced, and the Great Depression had affected even the very wealthy. The estate lingered on the market, even following several price reductions.

In 1940, following the suggestion of Franklin Roosevelt, the property was donated to the National Park Service. The donation included all of the original furnishings and artwork, which remain in the home. Although considered a small seasonal home by Vanderbilt standards, the Hyde Park mansion is all around outstanding, and not to be missed by anyone who loves architecture or interior design.

3 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback: